As we are not here considering Art History, but instead the universal distribution of archetypical ideas, we can just state that Max Beckmann (1884 – 1950) was a German Expressionist and a New Objectivist. He was, also, a traumatized veteran of the First World War. That Max Beckmann was indeed all these things, seems obvious when viewing his 1919 large oil paint masterpiece, “The Night”.

The painting depicts a scene of three thugs breaking and entering a gothic garret, and violating the inhabitants. The painting is crammed tight with angled distortions, conveying simultaneously dynamisms and frozenness. Objects become alive with unbearable morbid emotion, and the overall milieu of the painting reminds one of the psychological settings of some German Expressionist films – not least The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

Although the horrible happenings in the painting can be related to some of the severe social upheavals of the 1919 Germany, the artist himself has insisted that when considering “The Night”, one should not overlook “the metaphysical in the objective”. To be more precise, Beckmann wished to give “human beings an image of their destiny”, that is, a memento mori.

What makes this memento mori especially haunting is its quality of Abrahamic Immanence. This means that the painting distributes us Biblical characters, as archetypes inhabiting the eternal present, and vitally inherent in each passer-by we chance to meet. In the case of this painting, we meet here characters from the history of Christian painting

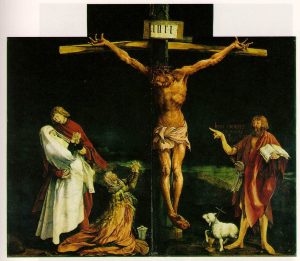

The man being hanged at the far-left side of the painting, has his facial expression and the twisted leg borrowed from Matthias Grünewald’s Christ in the artist’s early 14th Century Isenheim Altarpiece. The two figures are actually mirroring each other, with their head and foot twisting in opposite directions. Beckmann saw Grünewald as one of “the four great painters of manly mysticism”, the other three champions of this unsentimental religious art being Malesskircher, Bruegel and Van Gogh.

At the far- right of the painting we encounter a stereotypical brute, sporting a horseshoe moustache and a peaked cap. He is holding open the window with one hand, and crabbing a surprisingly serene looking female with the other. This ruffian is lifted straight from a detail in 13th Century Italian gothic fresco called “The Triumph of Death”. After inspecting this same horseshoe-mustached face first in a the 13th Century gothic apocalypse (at the lower right corner of the fresco, dressed in blue), and next, intruding from the outer darkness of the Weimar Republic night, and through a disturbingly angled window, to snatch away a dreamy blonde, one cannot help but to be overwhelmed by the feeling of the uncanny. Has Abrahamic Immanence ever before produced such a shadowy and timeless presence!

From the same gothic fresco, we find a depiction of a well-known Medieval memento mori -theme, The Meeting of the Three Living and the Three Dead (at the lower left corner of the fresco). It was told that there were three kings who lost their way in the forest during a hunt, and met with three living corpses, who reminded the kings of their mortality, and warned against life devoted solely to pleasure. Now, we meet similar living dead in Charnel Grounds of Buddhist Religious Art. The equally well-known characters are the executed corpses, the walking skeletons and the zombies. These are creatures that many have encountered only in horror fiction. But the monsters in the Charnel Grounds are not fictional, but philosophical; The corpses that are impaled or hanged or dismembered represent false ideas of the self, the zombies exemplify the realization of no-self, and the skeletons are symbols of the inherent emptiness of all things.

In the same way, the monstrous men inhabiting the almost Lovecraftian angles of Beckmann’s “The Night” are Philosophical Monsters. They are images of human destinies, immanent and uncanny through the centuries. But, although there is a universal aspect to these Philosophical Monsters, each one of the monstrous manifestations in art is also unique. The interesting question is, I think, what is the individual message of these specific monsters, the Philosophical Monsters of Max Beckmann’s painting. This is a question I leave to you, dear reader.

Beckmann has told that he once saw in his dream William Blake, who spoke these words: “Have faith in objects; do not let yourself be intimidated by the horror of the world”. Perhaps these words shall profit us, too, in our contemplation of “The Night”

This article has been partly inspired by two books: “The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art” (Palgrave Macmillan) by Charlene Spretnak, and “Expressionism” (Taschen) by Norbert Wolf.